#SimBlog: Out Of Hospital Cardiac Arrest

““Approx. 50-year-old, collapsed in public park. Bystander CPR and then management by pre-hospital provider from the police.””

Observations

A – No adjuncts

B – No effort

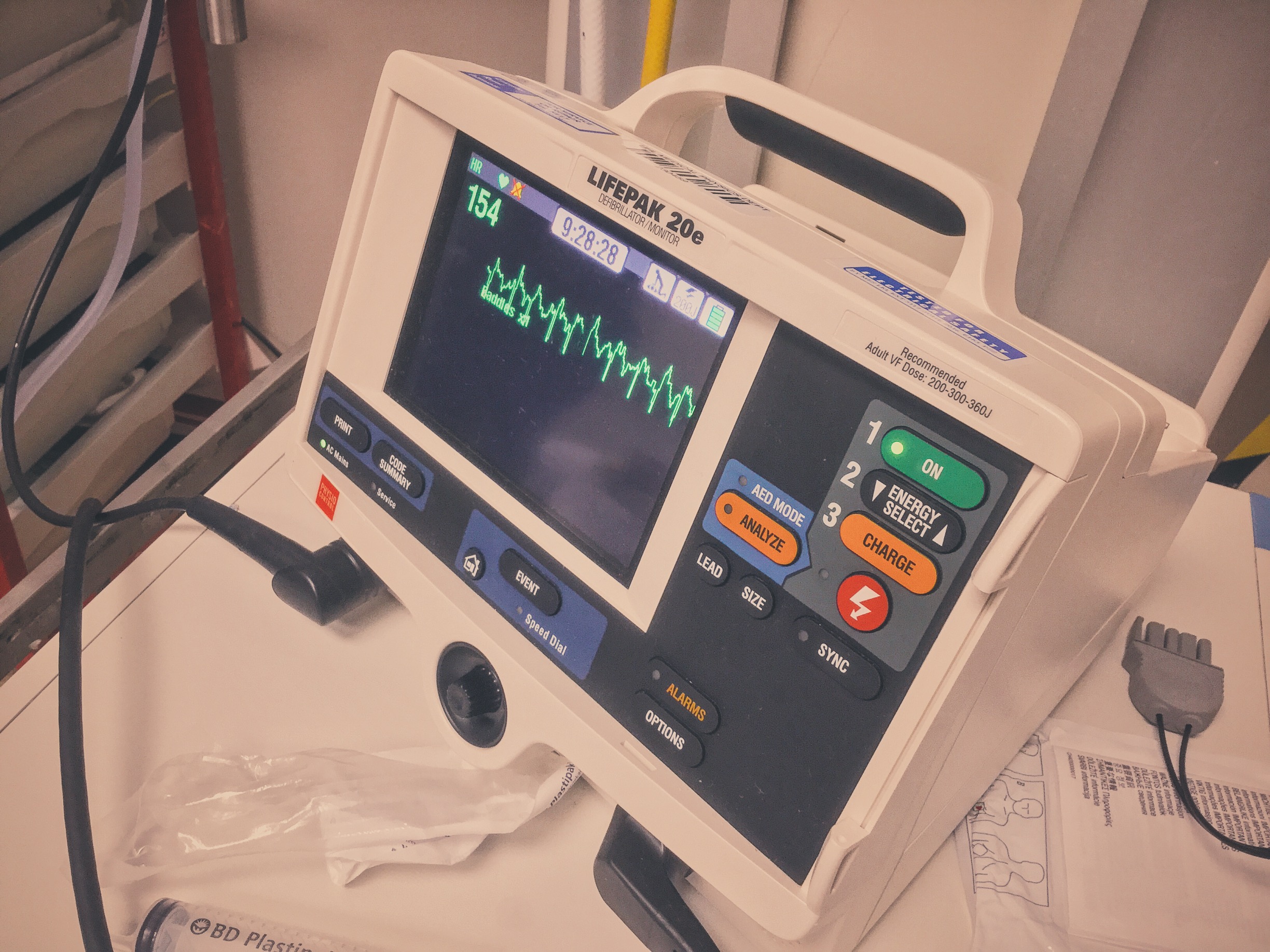

C – VT, no pulse

D – Unresponsive

E – No injuries, normothermic

Clinical Findings

No evidence of trauma or toxins

Why We Simulated?

Pre-hospital cardiac arrest represents the ultimate emergency, your patient is dead and it falls to you and your team to "bring them back". However this overly glamorous description plays into public perception (in part fuelled by the media) that with a few electric shocks and some chest massage a beating heart can be restored.

The perception of healthcare workers is often much bleaker, most will agree that resuscitation can be a brutal process and often ends with failure. But how bleak is it really? What is the survival rate for pre-hospital cardiac arrest and can we prognostic in the ED if we achieve a return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC)?

In the United States survival rates from out of hospital cardiac arrest range from 8% (all rhythms) to 17% (VF arrests). (Rea et al. 2004)

A meta-analysis of studies from Europe (Atwood et al. 2005) (including a 1996 study from Leicestershire (Hassan et. al 1996)) gave survival rates from 10.7 (all rhythms) to 21.2% (VF).

A more recent study looking at mechanical versus manual chest compressions in pre-hospital cardiac arrest found a 30 day survival rate of between 6 and 7%. for all rhythms (Perkins et al 2014).

Already we can see that survival rates are low but that VF carries a better rate of survival than other rhythms. If we do achieve ROSC are we able to prognosticate in the ED?

The following factors are often quoted as being associated with improved survival:

Shorter time to CPR

Shorter duration of resuscitation

Shockable rhythms (VF/ VT)

ETCO2 >10mmHG during CPR

Each of these makes sense, however these are not the only factors that need to be taken into account and their absence should not be taken as exclusion criteria for admission to critical care (Temple 2012).

However admission to critical care is often not as clear cut as it would first seem. The consensus is that neurological outcome cannot be fully assessed in the ED and should occur after 72 hours. It would therefore seem beneficial to take the majority of patients to critical care, however our patient's are becoming increasingly complex with multiple morbidities.

All of the following are associated with poorer outcomes post ROSC:

Metastatic malignancy

Non-metastatic malignancy

Sepsis

Dependent functional status

Pneumonia

Creatinine >130 mmol/litre

Age >70 yr

These also form the basis of the Prognosis After Resuscitation Score, however it should be noted this score was developed using patients following an in hospital cardiac arrest (M.H.Ebell 1992).

A sensible conclusion is that critical care should be considered for all patients post cardiac arrest unless they have co-morbidities or other features that preclude ITU admission. This however remains a vague description but is supported succinctly by Temple (2012):

"It would appear appropriate to err on the side of caution as temporarily prolonging the life of someone destined to a poor neurological outcome is less of a significant error than withdrawing care on someone who could make a good recovery.

The decision to admit to critical care should be primarily based upon a patient’s pre-morbid physiological status and wishes if known. Predicting potential recovery based on factors associated with the cardiac arrest can no longer be recommended."

Finally, there is also mounting evidence that for patients with no obvious non-cardiac cause of their arrest angiography and possibly PCI can be beneficial regardless of any evidence of STEMI on their ECG. The evidence behind this is summed up very well by the Resus Room Podcast.

Learning Outcomes

Minimise Time off of the chest when transferring to trolley.

Standardised Communication Tools Can Help optimise handovers.

Utilise the whole team, if you are short the pre-hospital team may be capable of helping out.

Positive Feedback

Managed scenario despite limited skill set of team provided.

Considered Post ROSC management including critical care and potential for PCI.

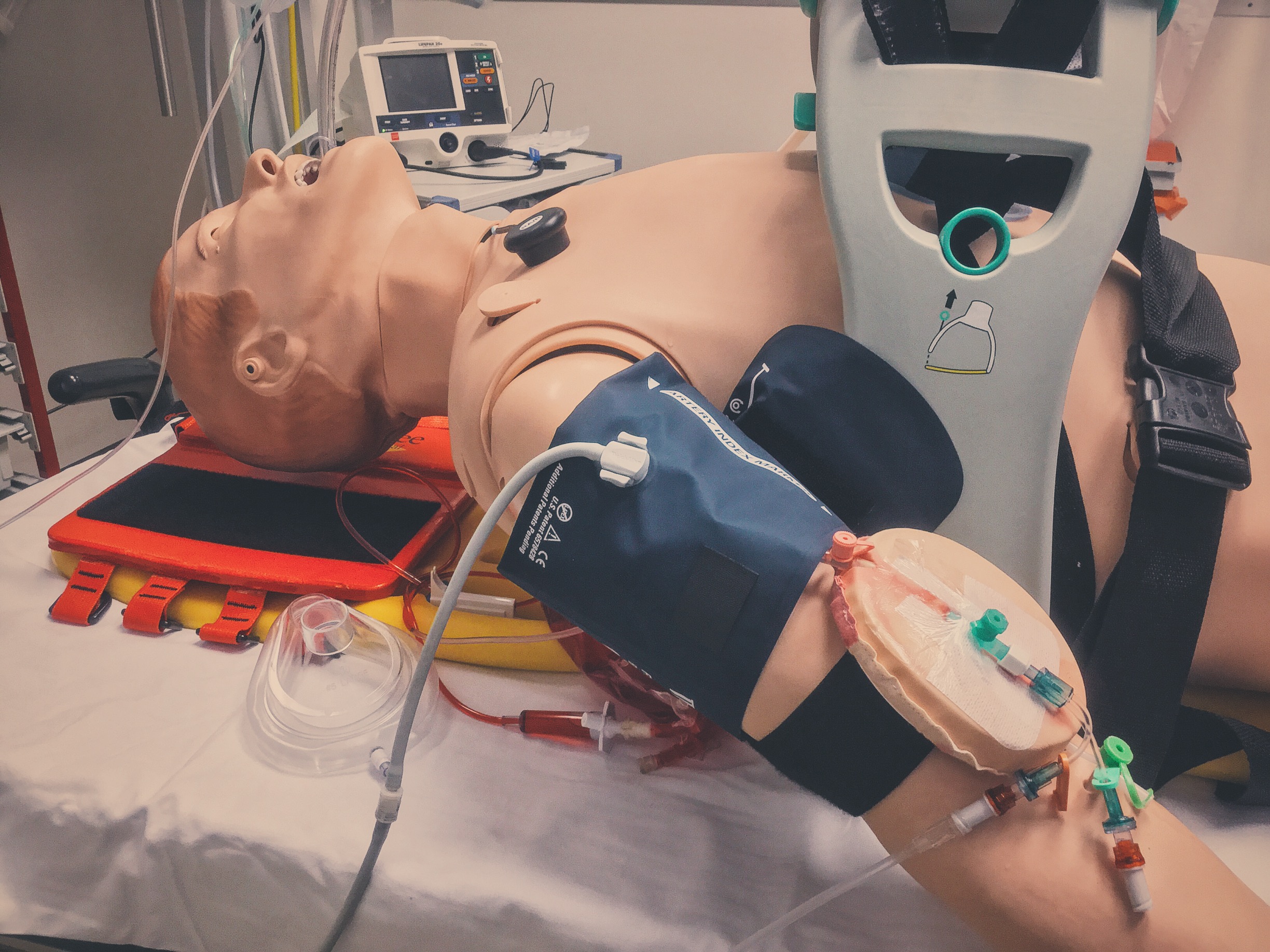

Utilised mechanical devices such as LUCAS and Ventilator to enable hands free resucitation.

References:

- A.Temple,R. Porter Predicting Neurological outcome and survival after cardiac arrest Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain, 2012, 12 (6): 283-287.

- C. Atwood, M.S. Eisenberg, J. Herlitzd, T.D Rea. Incidence of EMS-treated out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Europe Resuscitation Volume 67, Issue 1, October 2005, Pages 75–80

- M.H. Ebell Prearrest predictors of survival following in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a meta-analysis. J Fam Pract 1992 May;34(5):551-8.

- Prof Gavin D Perkins, MD, Ranjit Lall, PhD, Prof Tom Quinn, M Phil, Prof Charles D Deakin, MD, Prof Matthew W Cooke, PhD, Jessica Horton, MSc, Prof Sarah E Lamb, DPhil, Anne-Marie Slowther, DPhil, Prof Malcolm Woollard, MPH, Andy Carson, FRCGP, Mike Smyth, MSc, Richard Whitfield, BSc, Amanda Williams, MA, Helen Pocock, MSc, John J M Black, FCEM, John Wright, FCEM, Kyee Han, FCEM, Prof Simon Gates, PhD, PARAMEDIC trial collaborators Mechanical versus manual chest compression for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (PARAMEDIC): a pragmatic, cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet , Volume 385 , Issue 9972 , 947 - 955

- T B Hassan, F G Hickey, S Goodacre, G G Bodiwala Prehospital cardiac arrest in Leicestershire: targeting areas for improvement J accid emerg Med 1996;13:251-255

- T.D. Rea, M.S. Eisenberg, G. Sinibaldi, R.D. White Incidence of EMS-treated out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the United States Resuscitation, 63 (1) (2004), pp. 17–24

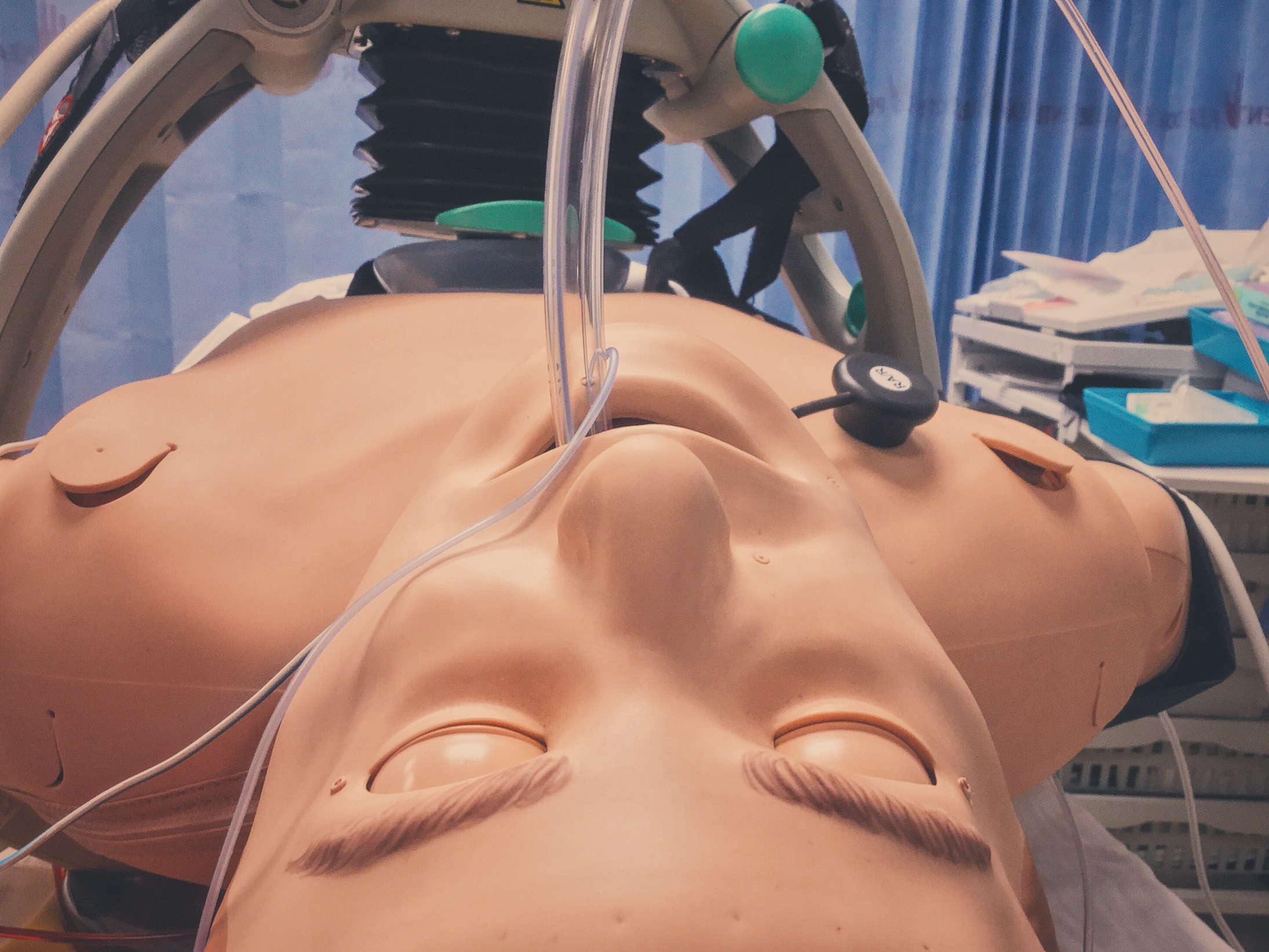

Special thanks to South Leicestershire Police for joining us for this simulation and to our Clinical Skills Department for the loan of a SimMan 3G. We hope to carry out further sims with colleagues inside UHL and beyond...