Major Incident Management

““By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail.””

Introduction

Major incidents form part of the HST curriculum and recent events mean that it is a likely question for the RCEM exams. Fortunately, most of us are unlikely to have encountered a major incident in real life so it is important that we cover the topic in other ways. For example, did you know that the curriculum states you should take part in more than one major incident exercise during HST?

Link to RCEM curriculum: Major Incident Management (HAP20)

Definition:

The curriculum states that we need to be able to define a major incident, this definition is taken from the Major Incident Medical Management and Support (MIMMS) manual:

"When the location, number, severity or type of casualty requires extraordinary resources..."

This is a fairly broad definition and allows for variability between hospitals. For example, two or three severely injured casualties might overwhelm the resources at one hospital, however, a larger hospital may cope with the same volume of injured patients. Equally, you may not be faced with severely injured patients but a large volume of minor wounded could overwhelm a lot of departments.

The other point that occurs to me is that most departments operating with exit block and increasingly long waits are unlikely to be able to cope with additional casualties, ie. an already overstretched system has little 'give' for a major incident.

We should also be aware that a major incident for pre-hospital services may not affect in-hospital services. For example, if the majority of casualties are killed on-scene they may not come to the ED.

There are further classifications that can be applied to a major incident that are worth being aware of but are probably of more use at an operational level:

Simple vs Compound Incidents: with simple incidents, infrastructure (i.e. rounds/communications) remains intact. With compound incidents, infrastructure is destroyed.

Minor, Moderate & Severe: this broadly relates to the number of casualties.

Compensated vs Uncompensated: a compensated major incident is when the mobilised resources are able to cope with the extra demand. In an uncompensated incident, they are not.

Activating a Major Incident:

The first thing your department is likely to hear of a major incident is when you receive a phone call from the Ambulance Service (probably from ambulance control). At which point you will be informed that a major incident has either been declared or is on standby.

The METHANE pneumonic makes for an easy SAQ

If you are unfortunate enough to be the one who picks up the phone it is important to ensure certain steps are taken (it's possible that your local policy is for switchboard to be contacted directly):

Obtain the relevant details – the pneumonic METHANE will help with this.

Inform the right people, i.e. the senior Doctor and Nurse in the department.

Confirm the Major Incident with the ambulance service (there exists the possibility of a hoax call so confirmation should be sought by calling ambulance control back).

Major Incident Plans

Your department or Trust should have a major incident plan that can be activated if the need arises. The curriculum states you should understand a typical major incident plan. Major incident plans should be "All-Hazard", i.e. one plan can be applied no matter what the type of incident.

The plan should also cover the whole of the incident from activation through to the debrief, including the well-being of staff involved. The effects of a major incident may be felt for weeks, months, and beyond. Equally different phases of the incident will stand down at different times. It may be that the pre-hospital phase is stood down fairly quickly but the hospital phase can persist for some time.

Broadly speaking the plan needs to cover the following:

Command and Control: this will outline who is in overall control and coordinating the response.

Key Staff: these should be assigned to job roles not specific individuals, for example senior surgeon which could refer to the Reg or the Consultant depending on who is currently in the hospital.

Key Staff Tasking: action cards should be available to direct staff as to their role and position within the hierarchy.

Team Definition: these will again be defined by action cards.

Communications: this applies to the notification of an incident, the cascade to staff as well as lines of communication during the event.

Key Area Selection: the standard roles of areas in the hospital may change, different triage categories will be managed in different areas, for example a fracture clinic adjacent to and ED may be used for P3 patients.

Infrastructure: the whole response will fail if there aren't systems in place to support it (e.g. catering, laundry, supply of equipment, childcare etc.)

The key part of your plan you will want to know is which priority patients will be managed where. It is likely that you will be allocated to work within one area that will look after one category of triaged patient. For example, Priority One patients (the sickest) will likely be managed in your Emergency Room (Resus); Priority Two patients will be managed in your Majors area; and Priority Three patients managed in your Minors area.

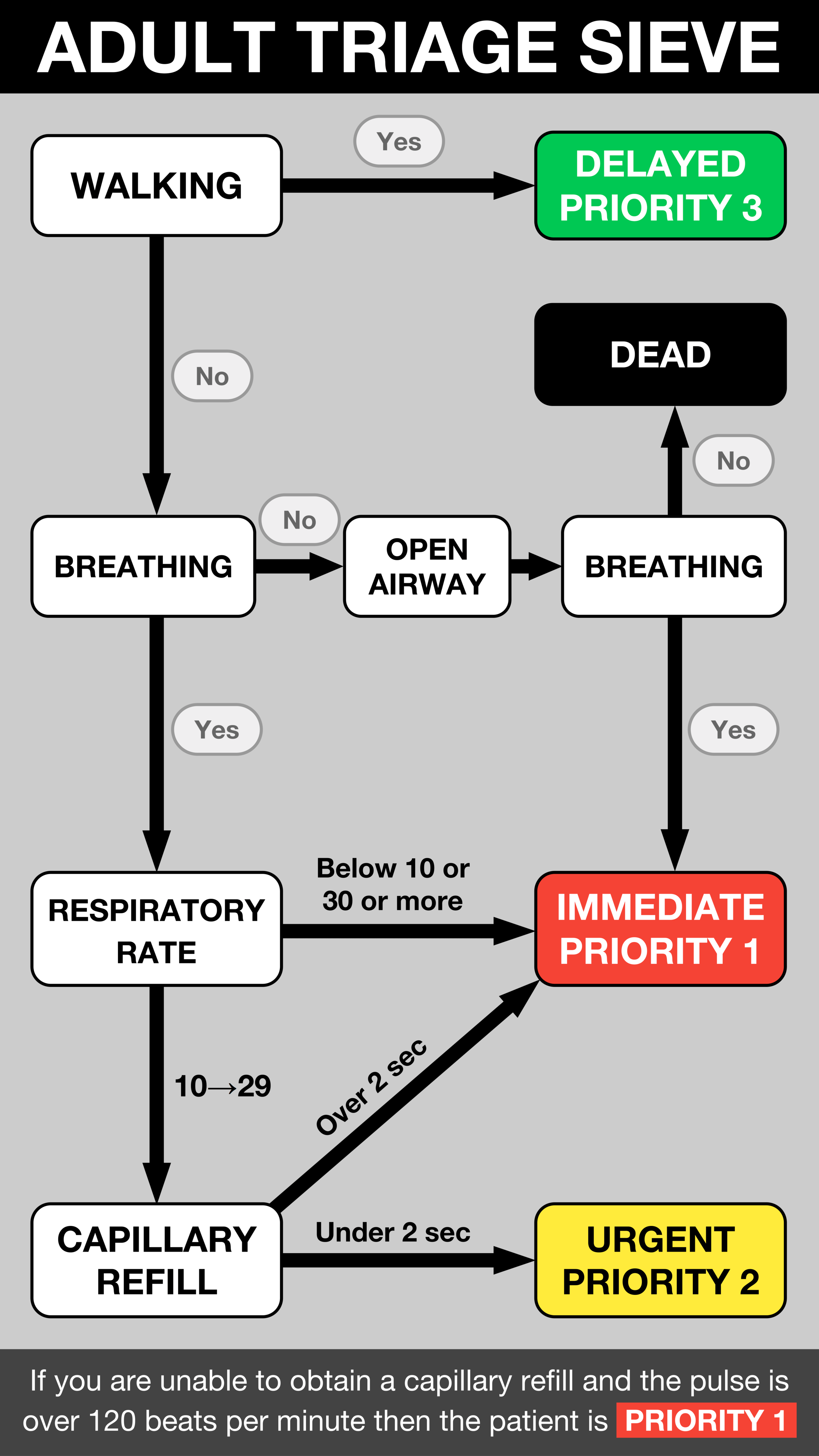

Deciding an appropriate priority for patients occurs in 2 stages, but remains a dynamic process;

On arrival at the front door of your department a senior EM physician will apply the Triage Sieve to the patients as they arrive.

A more detailed assessment using the Triage Sort will then occur and may reallocate some patients.

Another key point to understand is that any patient remaining in your department from prior to the activation of a major incident should be re-triaged using the same tools!

Triage (Sieve vs Sort)

When faced with a large volume of injured patients the role of Triage is important to identify those that need immediate treatment. Whilst the details of how to triage are important they should be explicitly stated within the action cards of those undertaking it. For our purposes it is worth understanding the differences between the Triage Sieve and Triage Sort methods:

The Triage Sieve is the first tool to be applied, either at the incident itself, but it may also occur at the receiving point at the hospital.

It is necessarily a "blunt tool" that can be performed in a standardised way when re-triage can occur further down the line.

From a practical perspective – due to the weight of the decisions being made – it is best performed by a senior clinician or (most likely) an ED consultant.

The Triage Sort is standardised and evidence based. It refines the identification of those requiring interventions and occurs following further assessment of the physiological status of the patient.

Scores are applied based on Respiratory Rate, Systolic BP, and GCS. The total score then gives the patient a triage status of Priority 1, 2 or 3. This may differ from the original status via the Triage Sieve. Triage Sort requires slightly more time to apply and therefore occurs further along in the process where there is likely to be fewer patients and more staff.

Further Reading:

- RCEM Learning: Major Incidents 1

- RCEM Learning: Major Incidents 2

- BMJ: Major incidents in England

CBRN

The curriculum also wants us to understand Chemical, Biological, Radioactive and Nuclear (CBRN) agents and their treatment – as well as the principles of decontamination. This is probably best covered as a topic on its own, however, more details on decontamination can be found in a previous blog post.

It is also worth summarising that CBRN usually refers to a deliberate act while the term HAZMAT (hazardous materials) is usually used in the context of an accident.